Trail Location 10: Evolution of South Fairmount

Walking Tour? VIEW THE TRAIL LOCATION IN GOOGLE MAPS >

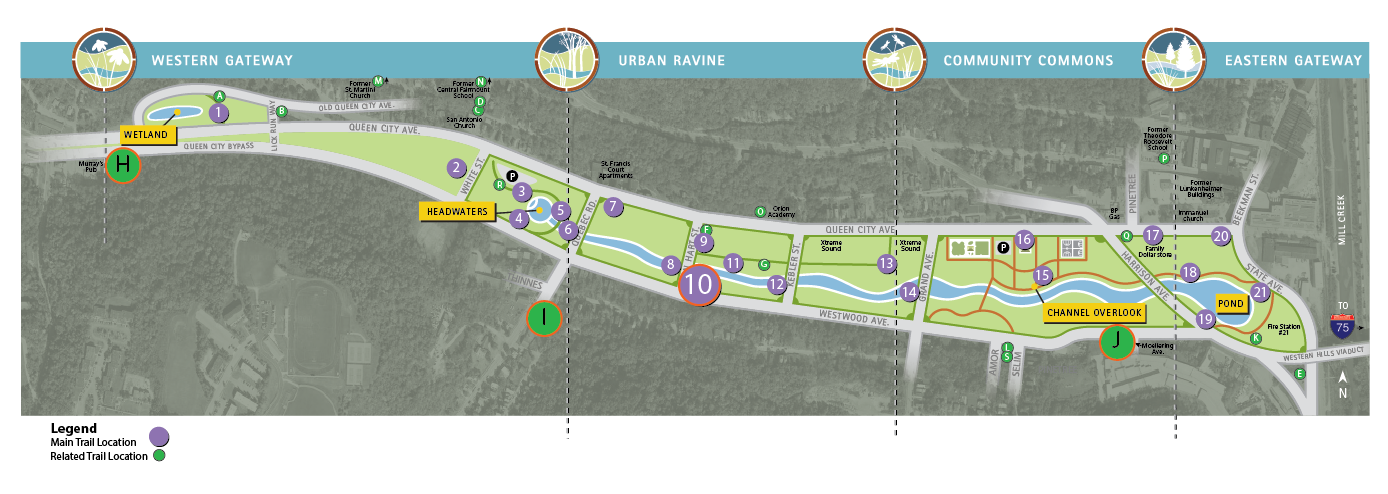

The Evolution of South Fairmount trail location includes a main stop at Trail Location 10 and three related stops:

- TRAIL LOCATION 10: EVOLUTION OF SOUTH FAIRMOUNT: IMMIGRANTS AND INDUSTRY >

- TRAIL LOCATION H: ST. PETERSBURG >

- TRAIL LOCATION I: ALL ABOARD! >

- TRAIL LOCATION J: NEIGHBORHOOD'S JOURNEY >

TRAIL LOCATION 10: EVOLUTION OF SOUTH FAIRMOUNT: IMMIGRANTS AND INDUSTRY

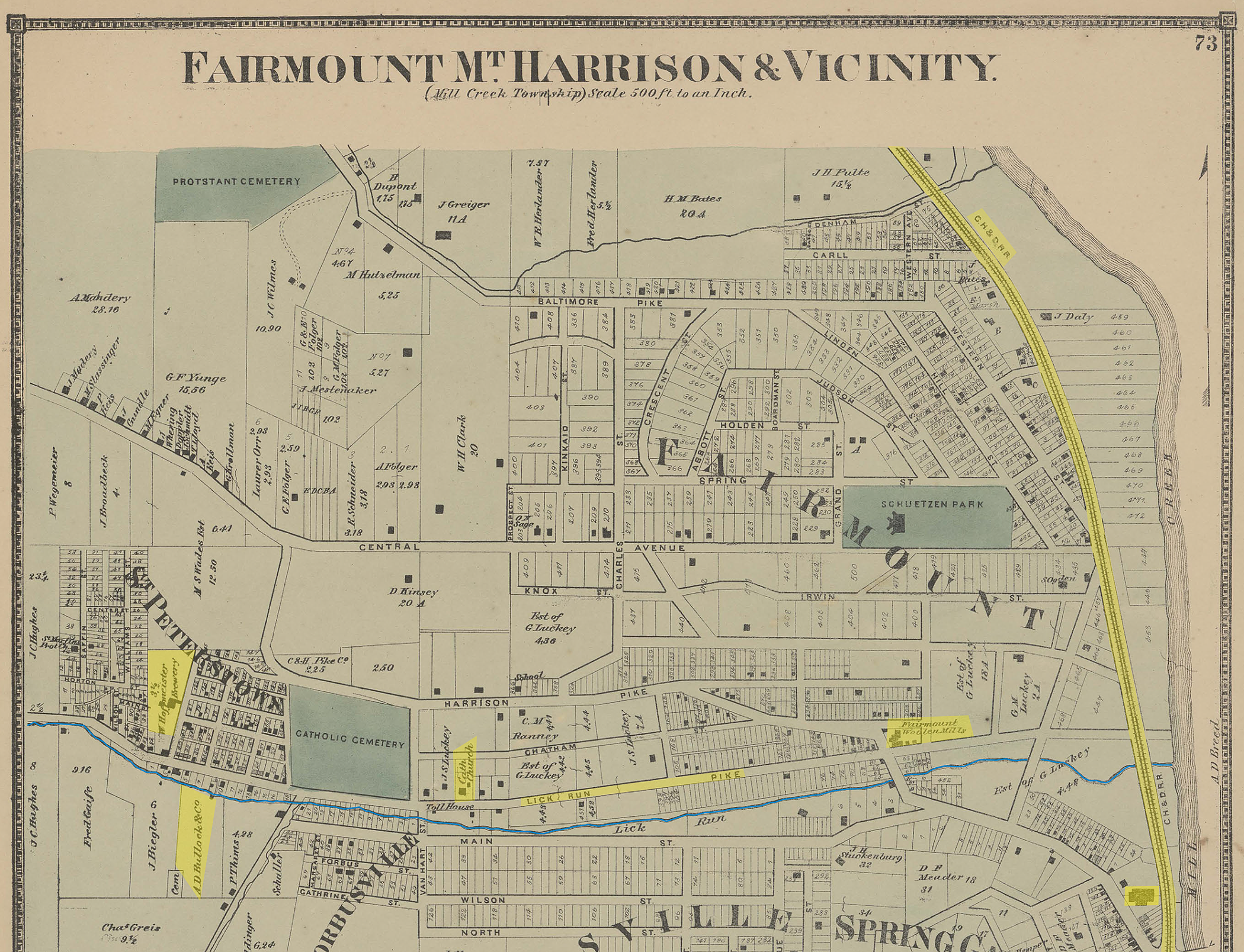

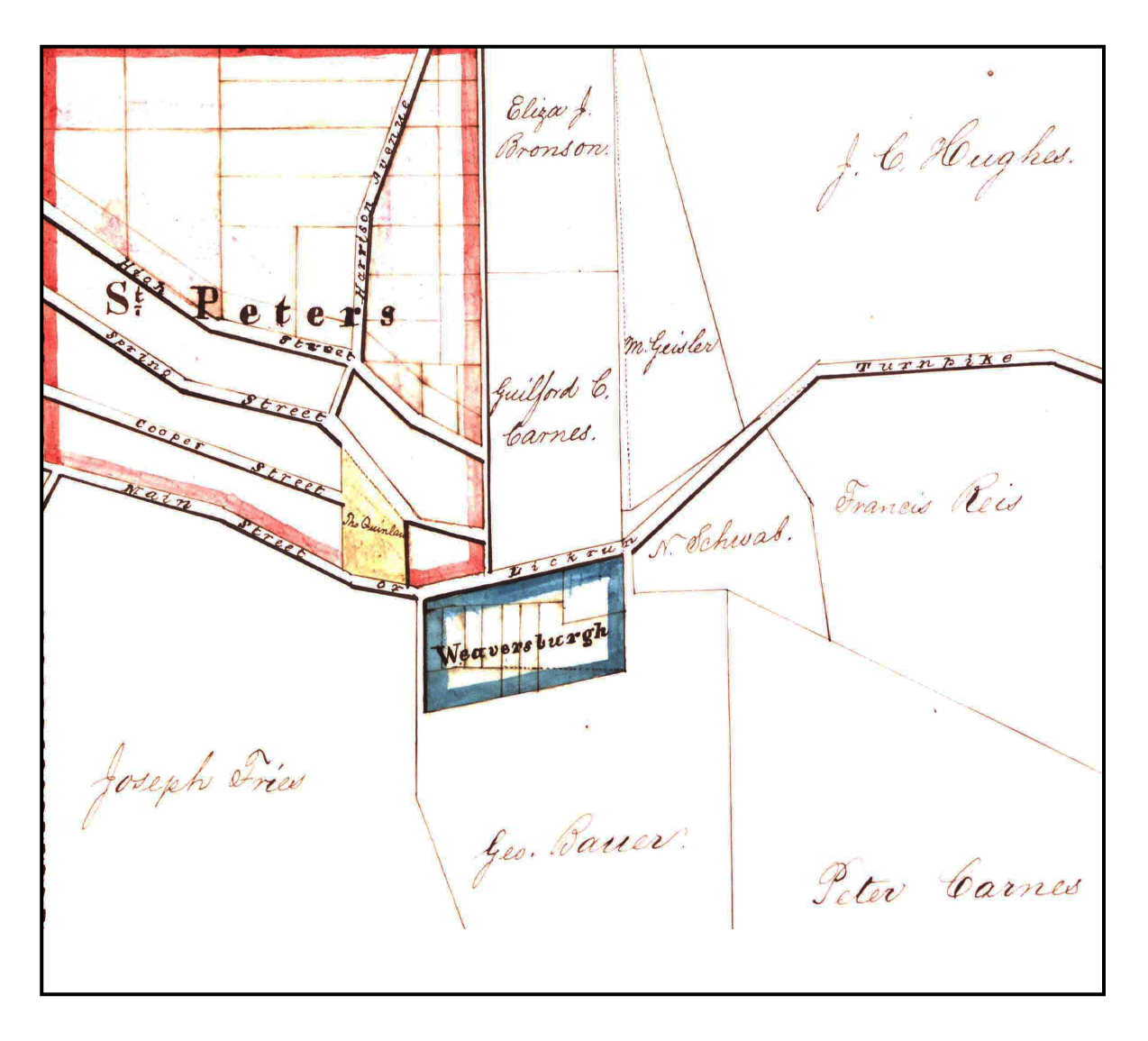

As one of Cincinnati’s “Seven Hills,” South Fairmount (known as Fairmount until the 1920s) holds a special place in the history of the Queen City. Fairmount began as a sprinkling of farm homes in the early 1800s, first settled by German immigrants. The main roads in what is now South Fairmount were Harrison Pike (now Harrison Avenue) and Lick Run Pike or Avenue (now Queen City Avenue).

That changed in 1851 after construction of the Cincinnati, Hamilton, & Dayton Railroad (CH&D), which skirted the west bank of Mill Creek and provided commuter service into the City of Cincinnati. In 1853, the Fairmount village was divided into large plots, with the hope the railroad would attract affluent residents wanting to build spacious suburban homes. Unfortunately, would-be commuters were not in love with the rugged and hilly terrain. Rather than courting suburban families, the plots were sold to entrepreneurial German immigrants, such as George Herancourt who opened the Philadelphia Brewery in 1848 and Bernard Adler who opened the Fairmount Woolen Mills in 1867.

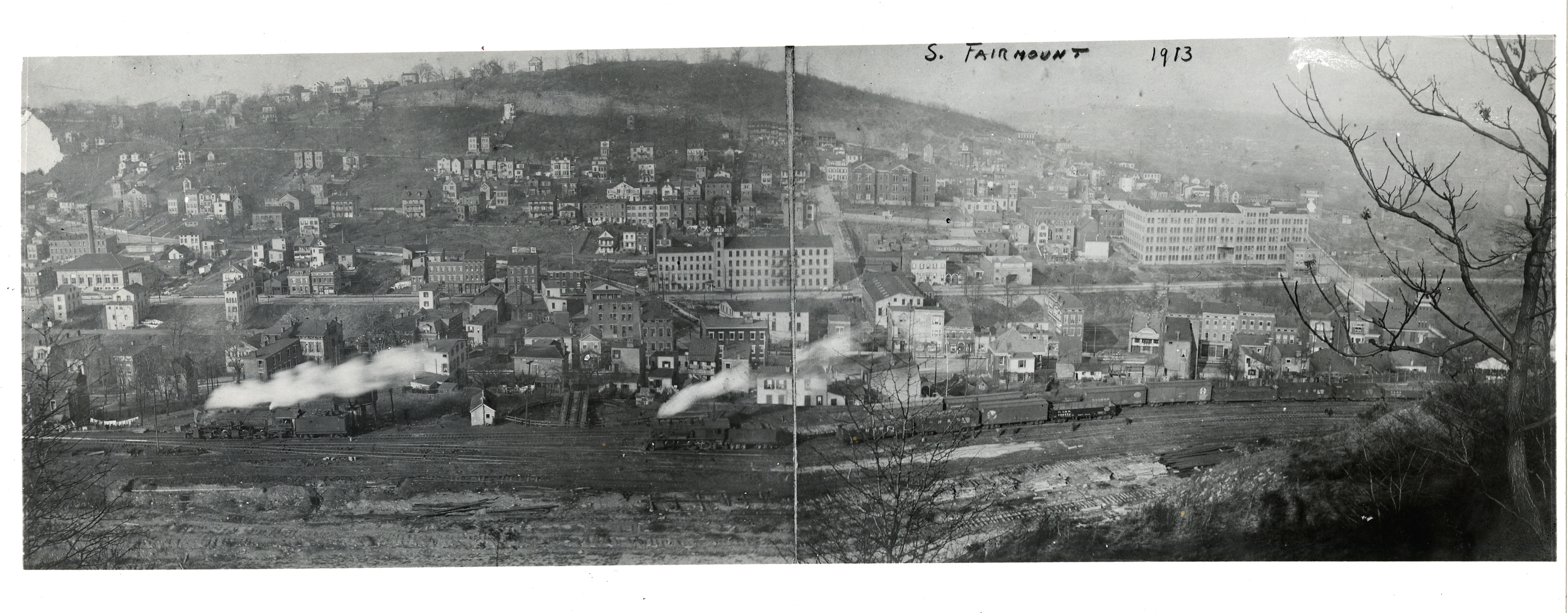

During the mid to late 19th century, employment opportunities at these and other factories attracted local residents who didn’t have the financial means to travel into Cincinnati on a daily basis (prior to the Cincinnati Street Railway System being constructed through Fairmount). By 1870, Fairmount became the largest village in the area, with approximately 70,000 residents. The mostly German immigrant population of Fairmount lived in more than 80 different buildings, mostly in small, simple brick or frame houses.

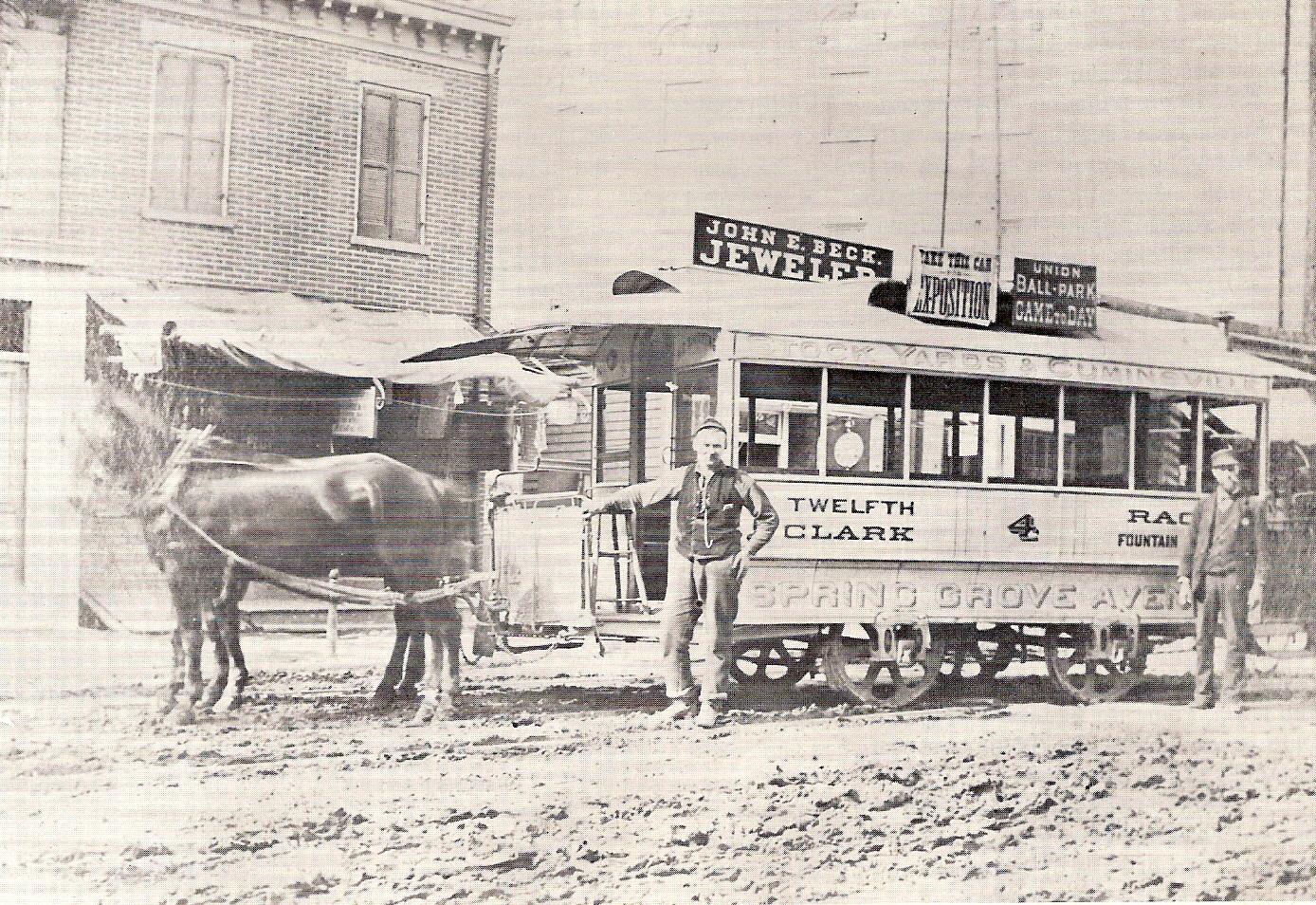

Fairmount’s population continued to grow throughout the remainder of the 19th century as a result of significant transportation improvements. A horsecar line built in 1879 was replaced by the more efficient electric streetcar system in the early 1890s. These new modes of mass transit linked the neighborhood to other areas of the city, including Westwood and Downtown, making travel more convenient and affordable. In the early 1920s, Fairmount’s population peaked at 15,000 residents, which was in large part due to the influx of Italian immigrants.

During this population boom, Fairmount grew into three distinct neighborhoods: South Fairmount, Central Fairmount, and North Fairmount. The oldest part of Fairmount, where early industries and homes were built, was previously known as Lickrun or St. Petersburg (or St. Peterstown), but is now commonly referred to as South Fairmount.

During the early 20th century, South Fairmount flourished, with a thriving commercial district occupied by small businesses such as groceries, pharmacies, hardware stores, barber and clothing shops, bakeries, theaters, saloons, and small restaurants. These businesses served South Fairmount residents, as well as thousands of others living in Cincinnati’s westside.

The end of World War II marked the beginning of the “American dream,” which encouraged young, more prosperous families to move to developing, auto-oriented suburbs. Reduced economic activity in the neighborhood resulting from suburbanization forced institutions and businesses to close. The decline in industry prompted U.S. labor markets to shift away from manufacturing, resulting in industries in Fairmount shutting down. The remaining businesses suffered another blow in the 1970s when Queen City and Westwood avenues were converted to one-way streets, and the Western Hills Viaduct was closed for repairs from 1976 to 1978.

- The construction of the CH&D railroad employed many immigrants of German and Irish descent, introducing them to the Fairmount neighborhood.

- After construction of the railroad was complete, many of these workers, especially the Germans, remained in the area, marking the birth of a neighborhood built by industry and immigrants.

TRAIL LOCATION H: ST. PETERSBURG

The arrival of German immigrants in Cincinnati exploded between 1830 and 1850. In 1830, just 5% of the population was German born. By 1840, that number had increased to 30%, and it more than doubled by 1850. The construction of new rail lines extending west from the city, as well as the development of the industrial businesses in Fairmount, attracted a large number of immigrants to this developing neighborhood.

In stark contrast to other foreign-born immigrants, Germans arriving in Cincinnati were predominantly Roman Catholic, and their spiritual, as well as social, needs could not be met by the established Protestant churches and schools. Thus, it was only natural that with such a great number of German immigrants, new Catholic schools and churches dedicated to those new residents would begin to appear all over the city.

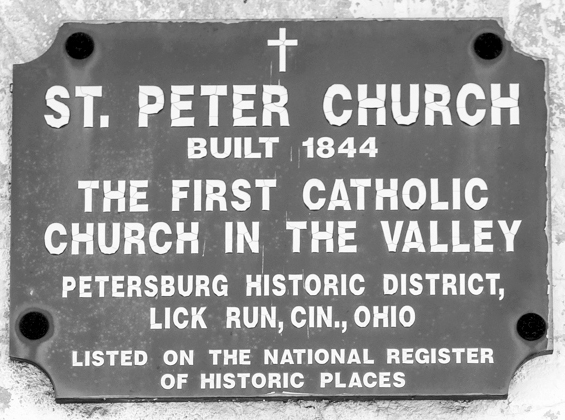

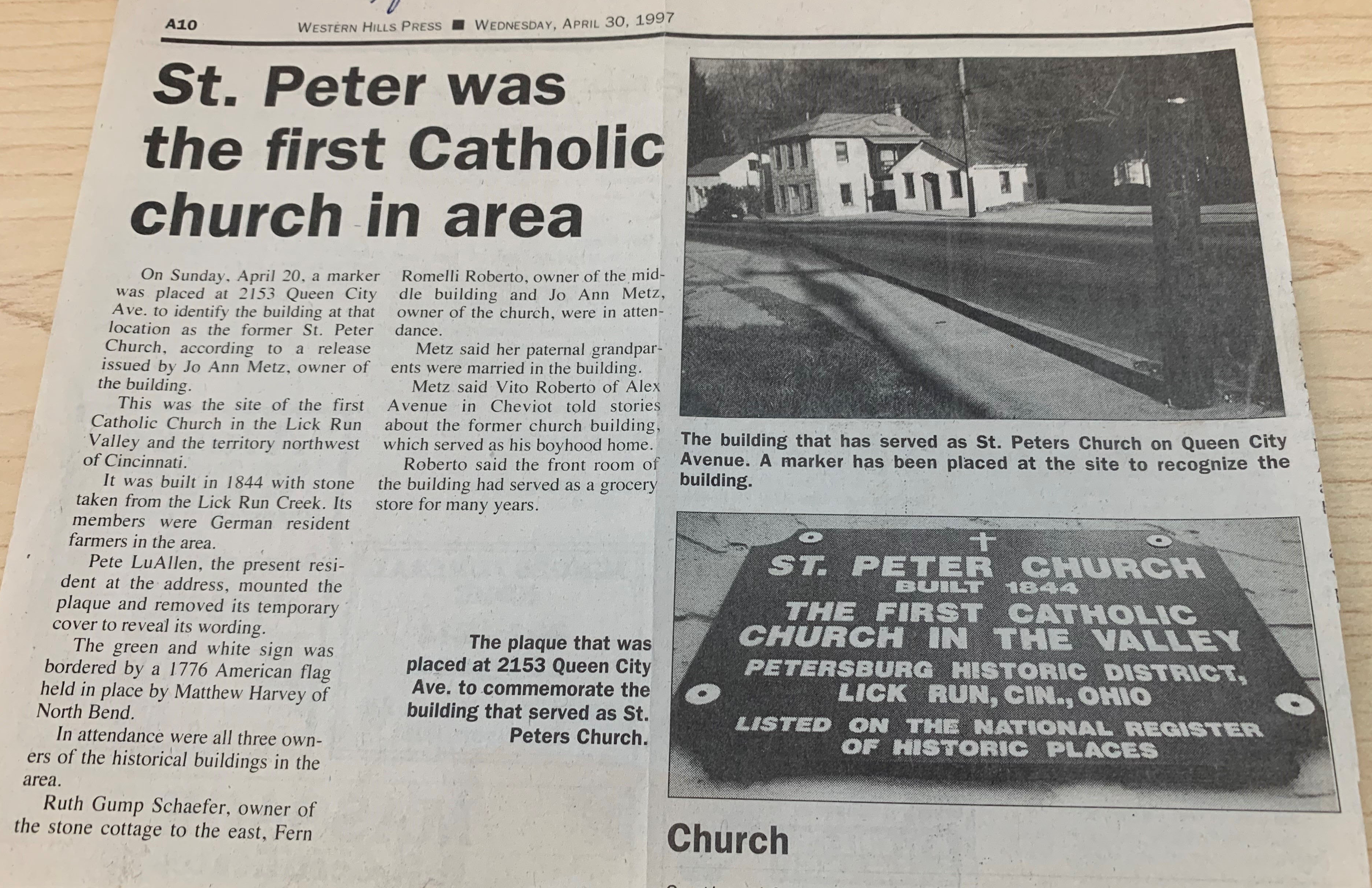

In the 1830s and 1840s, the western part of Fairmount was known as St. Petersburg, and it housed at least 20 Catholic families looking for a place to worship that was closer to home. As a result, in 1844, St. Peter Church opened at 2153 Queen City Avenue. This was the first church dedicated to German-born residents in the neighborhood. At first, the church also served as the school during the week, but a few years later, a separate school building was constructed at 2149 Queen City Avenue. The three buildings in the photo below, which are still standing, are the only remaining buildings that were part of the St. Petersburg settlement. All three are on the National Register of Historic Places. See the adjacent story about the Stone Home.

The church closed in 1868, as the population and congregation grew well beyond original expectations. At this point, this once-small religious community helped build the much larger St. Bonaventure—a true testament to the dedication of the growing population of this neighborhood.

Phil Sabatelli on the Catholic community and St. Petersburg:

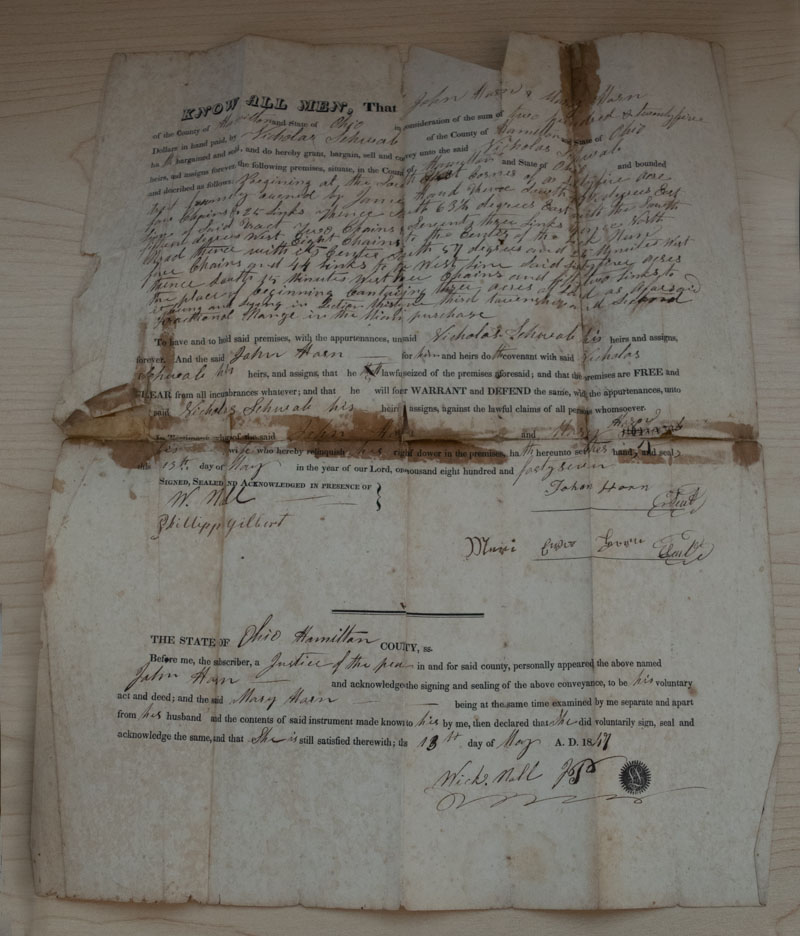

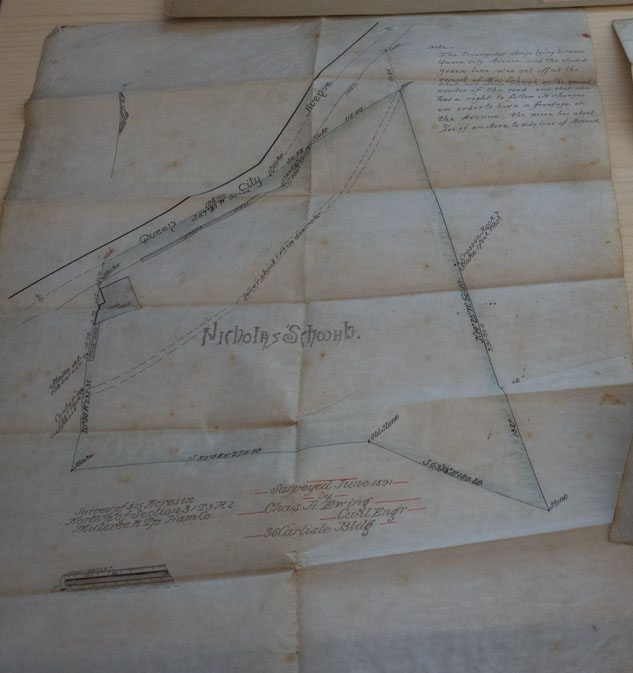

In 1849, Nicholas Schwab - formerly of Baden, Germany - purchased 3 acres of land along what is now the 2100 block of Queen City Avenue and began to build a home by hand out of stones found in the Lick Run stream which ran through the property. It was written that Nicholas looked like Abraham Lincoln only shorter.

While the home looks like a one-story home from the outside, it is actually a unique split level. The living and dining rooms are at ground level, with a kitchen and bathroom one step up, two bedrooms three steps up, and a cellar four steps down. Even the attic has two levels.

Nicholas was among a number of German immigrants who settled in this area, known as Lick Run or St. Petersburg, in the early 1840s. Those who were of the Catholic faith formed the German Catholic Congregation of Lick Run Road and began in 1843 to hold services in a small stone building at 2153 Queen City Avenue which they called St. Peter's Church. The community worshipped there until St. Bonaventure Church was built in 1869. They sent their children to school at the two-story stone building at 2149 Queen City Avenue. It is believed that Nicholas Schwab constructed both the church and the school and other stone homes in the community.

In November 1850, met Margaret Langfritz, a Bavarian girl "fresh off the boat." As the story goes, they met on a Sunday and married the following Thursday. Their courtship was short, but their marriage endured. They had 10 children before Nicholas died in 1881.

The second youngest of the 10 children, Elisabeth Barbara Schwab, continued to live at the stone home even after she married. Elisabeth and her husband, John Ludwig Schurr, had three children, among them Christine Margaret Schurr who was born in 1887.

Christine left the stone home after she married, but when her husband died in 1917, leaving her with a new baby daughter, she moved back in to live with her widowed mother and grandmother. Several years later, she remarried Rudy Gump, a City of Cincinnati fireman who lived across the street.

Rudy bought the stone home in 1922 from Christine's two brothers. It had no electricity or plumbing at the time. Rudy and Christine raised four children in the home.

When Rudy died in 1986, a daughter, Ruth (Gump) Schaefer, inherited the home. Ruth and her husband, Charles "Joe" Schaefer, had four children: Daniel Schaefer (deceased), Chris Shaefer, Maribeth (Schaefer) Harvey, and Frenly (Schaefer) Lister. Before she died in 2020, Ruth transferred ownership of the home to Maribeth's son, Andrew.

"It's very old, but it's a precious thing to our whole family," said Maribeth Harvey. "There's a stair from the dining room to the kitchen. It's an old log, and it's all worn down and smooth from our family stepping on it all these years."

Interview with the Stone Home ancestors:

Maribeth Harvey and her brother Chris Schaefer, talk about the Stone Home, which has been in their family since 1849.

Want to know more about the Stone Home? Visit the Photo Gallery, watch more videos, and learn how the Stone Home was saved in the late 1980s

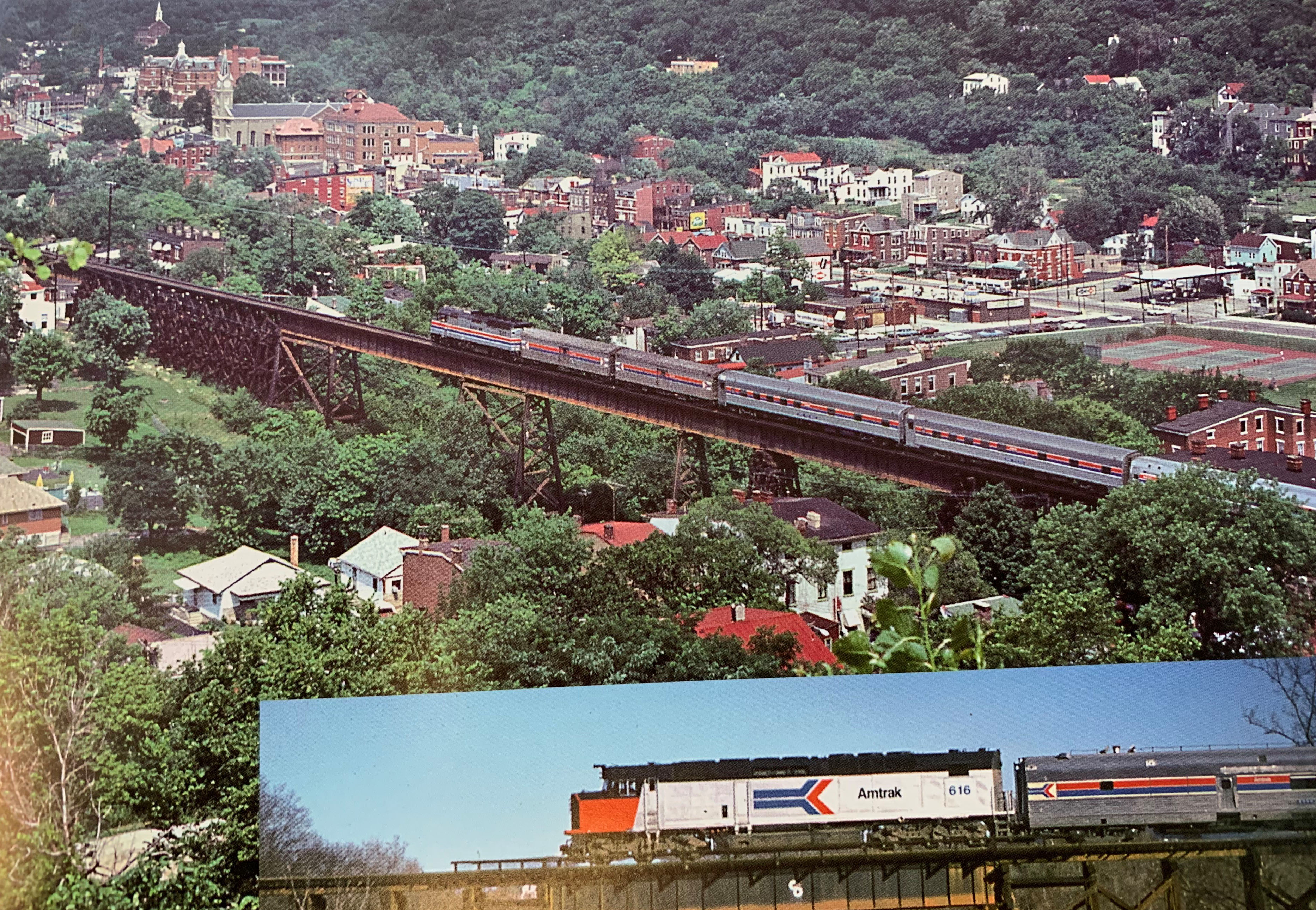

TRAIL LOCATION I: ALL ABOARD!

Throughout the 19th century, newly constructed railways spurred the development of existing suburban and rural towns located along the line.

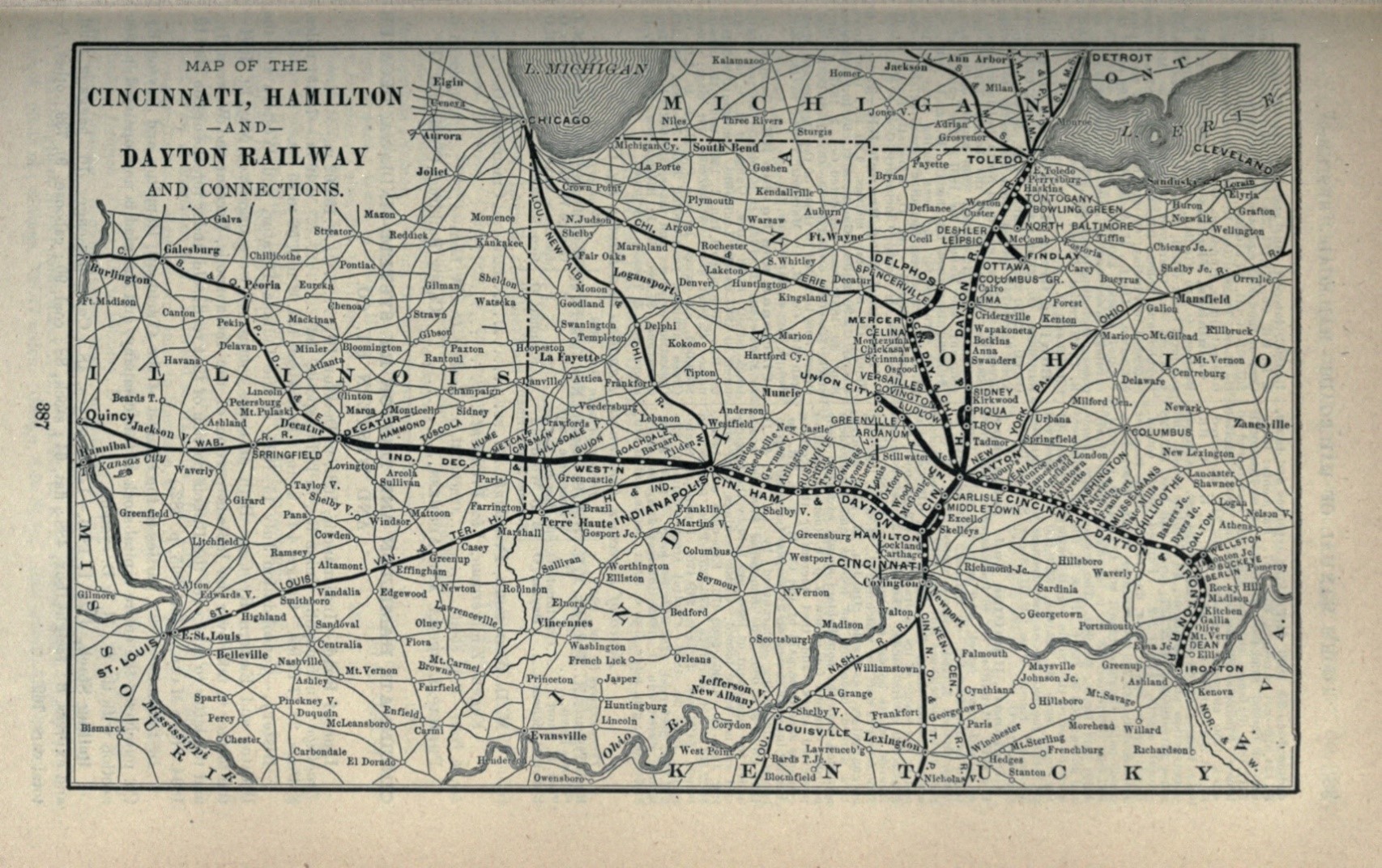

The Cincinnati, Hamilton, & Dayton Railroad (CH&D), which was built between 1846–1851, served as a commuter line between the cities of Cincinnati and Dayton, by way of Hamilton, Ohio. Not only did this new route ease travel for professionals with businesses in those cities, it encouraged wealthier families to reside outside the city, which introduced the concept of suburbanization.

The CH&D was the second railway to be constructed through Cincinnati, but it was the first line to pass through the Mill Creek Valley to points north of the city until reaching the cities of Hamilton and Dayton. In the 1860s, the CH&D began to invest in other railroads, linking a number of major Midwest cities to the Atlantic and Southern portions of the country.

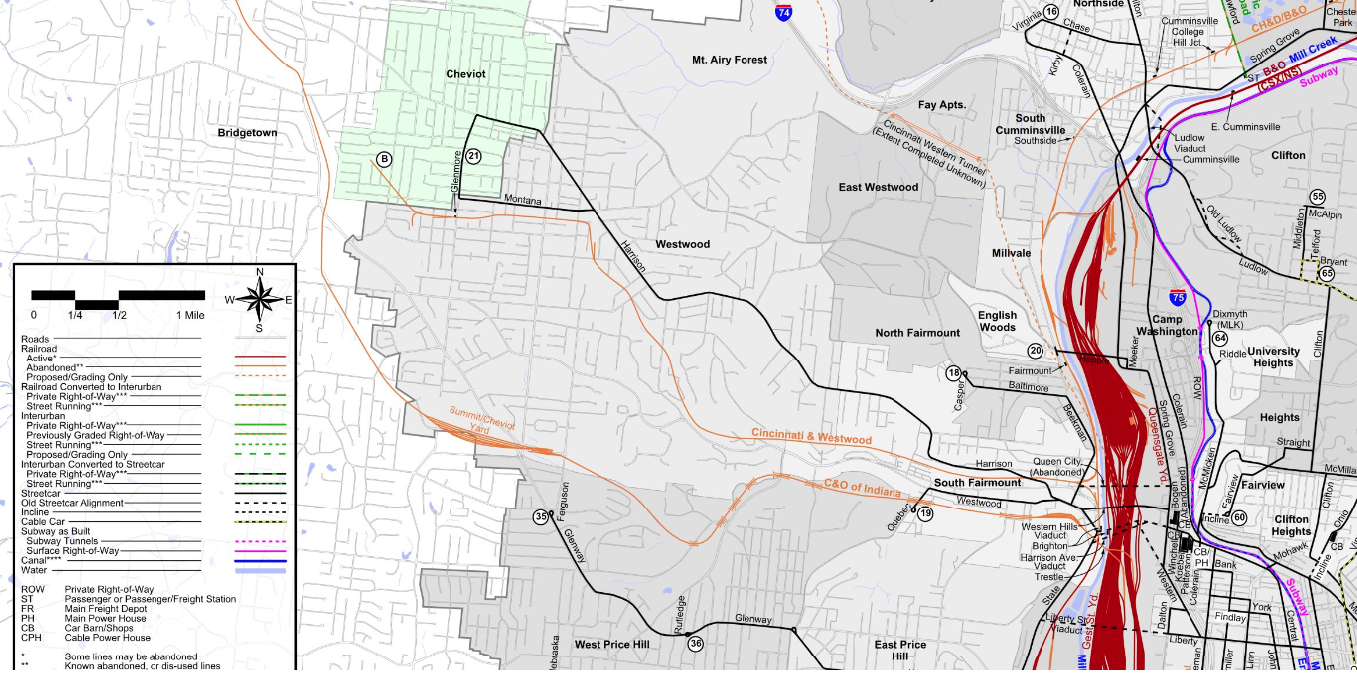

In 1909, the CH&D was bought by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and subsequently purchased by CSX Transportation in the late 1980s. The trainyard, now located below the Western Hills Viaduct, is still operational and serves as a major manufacturing transportation hub in Cincinnati. Portions of the old running track (any rail line that veers off the main line, often for industry-related purposes) are visible near the old Lunkenheimer Valve Co. plant complex, on Beekman Street near Tremont Street and Waverly Avenue. Because the old running track is mostly paved over, only the steel rails can be seen when traveling on Beekman.

In 1876, the Cincinnati & Westwood Railroad (C&W) was the second rail line to be constructed through Fairmount. The railroad was meant to serve commuters and help land speculators sell their plots to new, wealthy residents looking for a convenient way in and out of the city. This line, which opened in 1876, only ran a distance of 5.6 miles. After an unsuccessful first run, the line closed in 1886, only to reopen a year later after a reinvestment by James N. Gamble, son of one of the founders of Procter & Gamble and the last mayor of Westwood before it was annexed by the City of Cincinnati. Gamble’s contributions upgraded the railway from a narrow to a standard gauge line, which allowed the C&W coach cars to be coupled on the rear of CH&D trains.

In 1895, the Cincinnati Street Railway Company opened an electric line to Westwood, which became preferable to the C&W. The following year, passenger service via the C&W was suspended and, by 1924, the advent of motorized vehicles coupled with improved streetcar transit compelled the C&W to cease all operations.

TRAIL LOCATION J: A NEIGHBORHOOD'S JOURNEY

By the late 19th century, South Fairmount (which was called Fairmount until the 1920s) had approximately 8,000 residents with more to come. The arrival of the horsecar line on Westwood Avenue in the 1880s marked the beginning of a period of rapid growth in the neighborhood. Those who had resisted moving to Fairmount because of an expensive commute into the city via the Cincinnati, Hamilton, & Dayton Railroad now had a feasible and affordable way of getting to and from the city.

Fairmount's population soared again after the 1890s, when the electric streetcar replaced the horsecar line along Westwood Avenue. The population boom resulted in a construction frenzy. Multiple-story buildings emerged, combining businesses and storefront on the first floor with residential units on the upper floors. Local industries in the community also experienced a surge during the early part of the 20th century, as commuters loyal to the small family-owned businesses in the area would shop on their way to and from the city from adjacent neighborhoods, such as Westwood.

By the 1960s and 70s, population surges and development in the area were causing traffic problems in South Fairmount, as numerous commuters from the western suburbs travelled through the neighborhood on their way to the Western Hills Viaduct and downtown Cincinnati. In an effort to improve the traffic congestion, the City of Cincinnati converted Westwood and Queen City avenues into one-way east and west streets. This change made it much harder for patrons to shop in the neighborhood, causing a decline in the number of small, family-owned shops.